Other Primates of Borneo & Sumatra

The islands of Borneo and Sumatra are two of the most biodiverse areas on earth, known for their extraordinarily rich flora and fauna. Although much of the recent international attention has focused on the islands’ wild orangutans, the forests of Indonesia in fact contain over 10% of the world’s flowering plants, 16% of the world’s reptiles and amphibians, 17% of the world’s birds and 12% of the world’s mammal species (Wakker, 2004). Among these are over 20 species of primate.

OURF has always believed that the key to protecting orangutans is protecting their rainforest home, and ensuring that the remaining rainforests of Borneo and Sumatra remain as intact and inviolate as possible. But protecting orangutans is also important for the very future of that rainforest. Due to their ecological role as seed dispersers and the part they play in breaking up the dense rainforest canopy, studies have shown that rainforests with orangutans present, at their normal densities, can expect the presence of at least 5 other species of primate and hornbill, 50 different species of fruiting tree, and 15 species of liana (Rijksen & Meijaard, 1999). Some of the primate species found are some of the most extraordinary on earth.

Gibbons

Like orangutans, gibbons are apes, but, unlike orangutans, they are considered lesser apes, on account of their smaller body size. There are two species found in Sumatra, the white-handed gibbon (Hylobates lar vestitus) and the agile gibbon (Hylobates agilis), and two species found in Borneo, Muller’s Bornean gibbon (Hylobates muelleri) and the Borean white-bearded gibbon (Hylobates albibarbis), although it must be noted that some scientists consider the latter gibbon merely a sub-species of the agile gibbon.

Like orangutans, gibbons are apes, but, unlike orangutans, they are considered lesser apes, on account of their smaller body size. There are two species found in Sumatra, the white-handed gibbon (Hylobates lar vestitus) and the agile gibbon (Hylobates agilis), and two species found in Borneo, Muller’s Bornean gibbon (Hylobates muelleri) and the Borean white-bearded gibbon (Hylobates albibarbis), although it must be noted that some scientists consider the latter gibbon merely a sub-species of the agile gibbon.

Gibbons are the least known about and least studied of all the apes, and long term field studies have been hampered by the gibbons’ almost wholly arboreal lifestyle. Unlike orangutans, gibbons are incredibly fast movers, and swing through the canopy using only their arms, a form of locomotion known as brachiation. Living in tropical rainforests, they feed chiefly on ripe fruit, which makes up at least 58% of their diet (Bartlett, 2007), which they supplement with leaves, flowers and insects. Their small body size, a head and body length of between 18-22 inches and a weight of 4.5-7kg, means gibbons can reach the ends of branches, exploiting food sources more large bodied arboreal animals cannot (Redmond, 2008).

The fur colour and physical appearance of gibbons varies from species to species, and there is also often variation between members of the same species and between sexes. However, gibbons are unusual amongst apes for the low level of sexual dimorphism shown, with males and females being around the same size, and often hard to distinguish.

Gibbons are born after a gestation period of 7 months, and reach sexual maturity between the ages of 6-9 years, when they form monogamous pairings with a member of the opposite sex, which lasts for the remainder of their lives, occupying a home range of around 40 hectares (Redmond, 2008), although this varies depending on species and the presence of other species of primate (Bartlett, 2007). Territories are defended aggressively.

The interval between births is usually two to four years, so most gibbon groups will consist of no more than two adults and two or three young, adolescents leaving the family group upon maturity. Unlike other apes, gibbons do not make nests, either for day or night rest, instead sleeping while sitting on bare branches. To aid this adaptation, have thick, hard pads on their lower back, called ischial tuberosities (Bartlett, 2007).

Gibbons are also known for their distinctive vocalizations, which are believed to be used as a spacing mechanism, to defend territories and to attract mates, and their haunting melodies, usually sung in unison, are one of the most beautiful sounds in South East Asian rainforests.

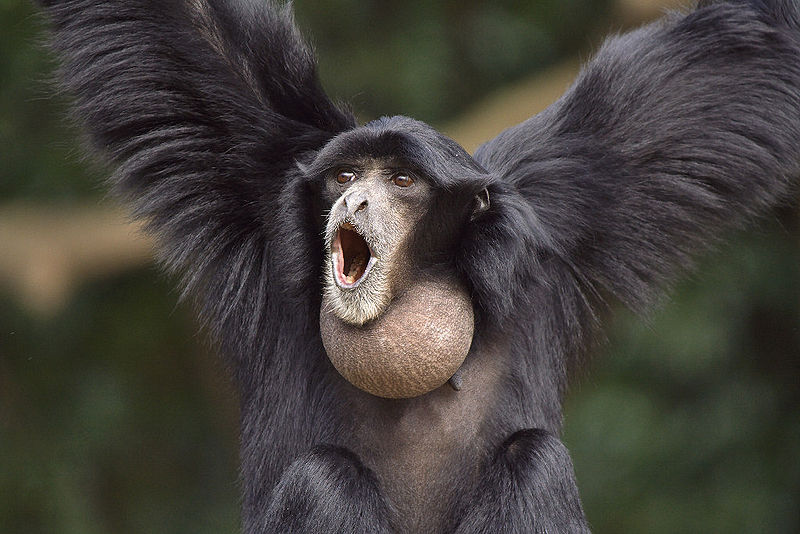

Siamang

The Siamang is a type of gibbon, but is classified in its own genus, as Symphalangus syndactylus. Found in Sumatra, siamangs are around twice the size of other gibbons, reaching around 40 inches in height and weighing up to 15kg, and are distinguishable by their long, shaggy black fur, and the large air sac, known as a gular sac, which sits under the throat of both males and females, and can be inflated to the size of their head, allowing them to make loud, resonating calls and songs.

The Siamang is a type of gibbon, but is classified in its own genus, as Symphalangus syndactylus. Found in Sumatra, siamangs are around twice the size of other gibbons, reaching around 40 inches in height and weighing up to 15kg, and are distinguishable by their long, shaggy black fur, and the large air sac, known as a gular sac, which sits under the throat of both males and females, and can be inflated to the size of their head, allowing them to make loud, resonating calls and songs.

The life history and adaptation of the siamang is similar to those of other gibbons, but these primates generally have smaller day ranges, and, unusually, male siamangs play a much more active role in the raising of the young than do members of the other gibbon species. Like all apes, they are long lived, and wild gibbons and siamangs may live until they are 30-40 years old.

Like orangutans, siamangs and gibbons are threatened by habitat loss and the pet trade, particularly for use as tourist attractions on the Asian mainland.

Proboscis Monkey

It would be hard to find a more unusually primate than the proboscis monkey, or the Dutch monkey, as it is known throughout Indonesia, on account of its alleged resemblance to the Dutch officials widespread throughout the country during the period of colonization. The proboscis monkey (Nasalis larvatus) is endemic to the island of Borneo, and lives in waterside forests, either coastal nipa palm, mangrove swamp, lowland riverine or peat swamp forests, and never at elevations higher than 800 ft (Redmond, 2008).

It would be hard to find a more unusually primate than the proboscis monkey, or the Dutch monkey, as it is known throughout Indonesia, on account of its alleged resemblance to the Dutch officials widespread throughout the country during the period of colonization. The proboscis monkey (Nasalis larvatus) is endemic to the island of Borneo, and lives in waterside forests, either coastal nipa palm, mangrove swamp, lowland riverine or peat swamp forests, and never at elevations higher than 800 ft (Redmond, 2008).

The body of the proboscis monkey is a reddish brown, with white-grey legs, belly, tail and rump. Juveniles are born with a blue face, which becomes pink at the age of three. Males of this species have a large, protruding nose, which can reach up to 7 inches long, and is believed to be used to attract females and to act as a resonating chamber to enhance vocalizations. Females also have large noses, although these are generally smaller than males, and are upturned. They have a head and body length of between 24-30 inches, and males can weigh up to 20kg (Redmond, 2008). Unusually, males of this species have permanently erect penises, a peculiar trait that still baffles scientists.

The digestive system of the proboscis monkey is divided in to compartments, with bacteria that neutralizes the toxins of certain leaves, and, as such, leaves make up the majority of their diet, with fruit and seeds also consumed (Nowak, 1999). Their diet has left them with a large pot belly, which weighs about a quarter of their whole body weight.

These monkeys live in a harem of one adult male, several females and their offspring, groups that can be as large as 23 animals. Proboscis monkeys are not territorial and may meet up with other groups, to feed or travel together, and they often sleep in neighbouring trees. They are extremely proficient swimmers, and will often swim across rivers to reach the opposite bank, one member of the group jumping in first to test the water. Young are born after a gestation period of 5 months, and sexual maturity for females is reached at 3-5 years, with males reaching maturity at 5-7 years.

Widespread forest conversion has seen these primates placed on the IUCN endangered list, but it is hoped their increasing popularity with tourists, and the ease with which they can be spotted from boats, could lead to more concerted conservation efforts.

Macaques

Of all the primates, macaques almost certainly have the worst reputation, being considered a pest throughout much of their range, which is the widest of any non-human primate. But their pest-like status is simply a result of their extraordinary resilience and adaptability, and their ability to thrive in almost any environment.

Of all the primates, macaques almost certainly have the worst reputation, being considered a pest throughout much of their range, which is the widest of any non-human primate. But their pest-like status is simply a result of their extraordinary resilience and adaptability, and their ability to thrive in almost any environment.

There are two species of macaque found in both Borneo and Sumatra, the pig tailed macaque (Macaca nemestrina) and the long tailed macaque (Macaca fascicularis), which are found throughout primary and secondary forest, coastal mangroves, swamp and riverine forest, and even some urban situations (Nowak, 1999).

Pig tailed macaques have olive brown fur over their bodies, with white undersides and a black patch on top of their heads, with males of this sexually dimorphic species having a head and body length of 19.4 to 22.2 inches, and weighing 6.2-14.5kg. Females are considerably smaller, weighing between 4.7 & 10.9kg. Long tailed macaques are the smaller species, with males weighing between 4.7-8.3kg. They are grayish in colour, and have hair that sweeps back over their forehead, creating a rather cute looking crest of hair above their heads. Both species of primates are named after their distinctive tails.

Pig tailed macaques have olive brown fur over their bodies, with white undersides and a black patch on top of their heads, with males of this sexually dimorphic species having a head and body length of 19.4 to 22.2 inches, and weighing 6.2-14.5kg. Females are considerably smaller, weighing between 4.7 & 10.9kg. Long tailed macaques are the smaller species, with males weighing between 4.7-8.3kg. They are grayish in colour, and have hair that sweeps back over their forehead, creating a rather cute looking crest of hair above their heads. Both species of primates are named after their distinctive tails.

Both species of macaque are largely frugivorous, and also eat insects, seeds, young leaves, leaf stems, dirt and fungus, with long tailed macaques known to feed on crabs, frogs, shrimp and octopus when foraging in coastal mangroves. Like all other species of macaque, they live in large social groups, sometimes as strong as 100 individuals, which break in to smaller groups for foraging, and social groups for both of these species are multi-male but female dominated.

Although not considered endangered, macaques are the focus of increasing animal welfare efforts, as they are the most common primates used for invasive medical research.

Leaf monkeys, Langurs and Surilis

Langur means ‘having a long tail’ in Hindi, and almost all species of langur monkey, and their relatives the leaf monkeys and surilis, live up to this name, having long, slender tails often longer than their bodies. The langurs, leaf monkeys and surilis are divided in to three separate genus groups, and there are up to 9 separate species on both Borneo and Sumatra.

Langur means ‘having a long tail’ in Hindi, and almost all species of langur monkey, and their relatives the leaf monkeys and surilis, live up to this name, having long, slender tails often longer than their bodies. The langurs, leaf monkeys and surilis are divided in to three separate genus groups, and there are up to 9 separate species on both Borneo and Sumatra.

The life histories and appearance of leaf monkeys, langurs and surilis differ from genus to genus and species to species, but the species found in Borneo and Sumatra are diurnal, arboreal tropical rainforest dwellers, and feed on leaves, seeds, fruit, shoots, flowers, bark, stems and fungi. Two species of monkey in Borneo, Hose’s langur (Presbytis hosei) and the red leaf monkey (Presbytis rubicunda), have been seen occasionally descending to the forest floor to visit natural mineral sources, and have a daily foraging range of around 500-800 metres (Nowak, 1999). In Sumatra, Thomas’s langur also descends to the floor to feed on mature rubber seeds and durian fruits.

The life histories and appearance of leaf monkeys, langurs and surilis differ from genus to genus and species to species, but the species found in Borneo and Sumatra are diurnal, arboreal tropical rainforest dwellers, and feed on leaves, seeds, fruit, shoots, flowers, bark, stems and fungi. Two species of monkey in Borneo, Hose’s langur (Presbytis hosei) and the red leaf monkey (Presbytis rubicunda), have been seen occasionally descending to the forest floor to visit natural mineral sources, and have a daily foraging range of around 500-800 metres (Nowak, 1999). In Sumatra, Thomas’s langur also descends to the floor to feed on mature rubber seeds and durian fruits.

The head and body length of these monkeys is between 16-33 inches, and they weigh between 5-8.1kg (Redmond, 2008; Nowak, 1999). They have a gestation period of around 6 months, and are believed to reach sexual maturity after a few years. The species found on Borneo and Sumatra usually live in groups consisting a single male and one or two adult females, although in some species, such as Thomas’s langur, groups with two adult males have been observed. Lone males and small all male units have been observed, as juvenile males disperse from their natal group on sexual maturity (Nowak, 1999), as have monogamous pairings (Kirkpatrick, 2007).

The head and body length of these monkeys is between 16-33 inches, and they weigh between 5-8.1kg (Redmond, 2008; Nowak, 1999). They have a gestation period of around 6 months, and are believed to reach sexual maturity after a few years. The species found on Borneo and Sumatra usually live in groups consisting a single male and one or two adult females, although in some species, such as Thomas’s langur, groups with two adult males have been observed. Lone males and small all male units have been observed, as juvenile males disperse from their natal group on sexual maturity (Nowak, 1999), as have monogamous pairings (Kirkpatrick, 2007).

Although relatively little is known about the various species of langur monkeys, leaf monkeys and surilis in Borneo and Sumatra, all are threatened by deforestation, forest conversion and hunting, and there is a danger they may become extinct before the full complexity of their social systems is known.

Slow loris

With their large, forward facing eyes, small wooly bodies and tightly clinging hands and feet, with their human like nails, slow lorises are among the most unusual looking primates. In fact, so beguiling were these creatures to Dutch officials, their popular western name derives from the Dutch word for clown, ‘loerus’. Highly prized as pets throughout their range, slow lorises are, along with the tarsier, the oldest and most primitive primates found in Borneo and Sumatra.

With their large, forward facing eyes, small wooly bodies and tightly clinging hands and feet, with their human like nails, slow lorises are among the most unusual looking primates. In fact, so beguiling were these creatures to Dutch officials, their popular western name derives from the Dutch word for clown, ‘loerus’. Highly prized as pets throughout their range, slow lorises are, along with the tarsier, the oldest and most primitive primates found in Borneo and Sumatra.

The taxonomic status of the slow lorises has long been a source of confusion, hampered by the scarcity of wild loris studies, but there are now believed to be two separate species inhabiting the forests of Borneo and Sumatra. The Bornean slow loris (Nycticebus menagensis) is found on the island of Borneo, and the greater slow loris (Nycticebus coucang) is found on the island of Sumatra, with both species inhabiting primary and secondary forest, wooded savannas and even plantations (Redmond, 2008). It was originally thought that there were just two species of loris found on these islands, but in late 2012, authors discovered that Bornean slow lorises had different facemask patterns depending on their geographical location, and that these facemasks, particularly the amount of white on the face, are sufficiently different to indicate different species; hence, as well as N. managensis, N. bancanus, N. borneanus and N. kayan are now recognised as different species of Bornean slow lorises (Munds et al, 2013).

The Bornean slow loris is one of the smallest loris species, weighing 0.26-0.3kg, and is covered in pale golden to red fur. It is distinguishable by the relative lack of markings on the back of its head, having instead a soft brown crown. In comparison, the greater slow loris weighs 0.59-0.68kg, has a darker, deep red fur, and dark rings around the eyes, which meet a dark dorsal stripe on the back of the head.

Slow lorises are slow moving, arboreal and nocturnal, and feed on a diet of fruit, seeds, leaves, bark, fungi, gums, shoots, flowers, birds’ eggs insects, small vertebrates and invertebrates (Redmond, 2008). During the day they sleep curled up in branches.

Little is known of the slow loris social systems, although they are thought to be largely solitary creatures, although groups have been observed when home ranges overlap, and relations between males are thought to be highly antagonistic. Slow lorises are born after a gestation period of around 6 months, and sexual maturity is reached between 17 and 24 months, at which time they disperse from their mothers. The lifespan of wild slow lorises has not been determined, but it is believed to be between 20-30 years.

Incredibly popular as pets, slow lorises are the only primate known to be poisonous, having glands on their arms that secrete a substance that contains toxins to paralyze prey. Their status in the wild is believed to be endangered, although the lack of concrete data means exact figures and population estimates are difficult to determine.

Tarsier

Tarsiers are small nocturnal primates found throughout South East Asia, and known for their huge round eyes, which are larger, relative to the size of the head, than in any other species (Redmond, 2008). Just one species of tarsier is found in Borneo and Sumatra, the Horsfield’s tarsier (Tarsius bancanus), and it is found in both primary and secondary rainforest, as well as coastal forest and mangrove associations.

Tarsiers are small nocturnal primates found throughout South East Asia, and known for their huge round eyes, which are larger, relative to the size of the head, than in any other species (Redmond, 2008). Just one species of tarsier is found in Borneo and Sumatra, the Horsfield’s tarsier (Tarsius bancanus), and it is found in both primary and secondary rainforest, as well as coastal forest and mangrove associations.

Like lorises, tarsiers are small, unusual looking primates, with a head and body length of between 34-63 inches. Unlike lorises, however, they are agile and fast moving, known for being able to jump extraordinary distances between trees. Their leaping ability stems from their powerful legs, which are one and a half times the length of the head and body combined (Redmond, 2008). Entirely carnivorous, tarsiers cling vertically to branches, catching and eating large insects such as beetles, grasshoppers, cockroaches, butterflies, moths, praying mantis, ants, phasmids and cicadas, as well as bats, frogs and snakes.

Tarsiers are born after a gestation period of 6 months, and reach sexual maturity around 1. Surprisingly, the social system of the horsfield tarsier is similar to that of an orangutan, with the female raising the young until it leaves the natal home range upon sexual maturity, establishing its own territory. Male home ranges, of between 2-8-11 hectares, overlap those of several females, and it is likely that the male will mate with all females in his home range, although he will play no active part in the raising of any young. Territories are defined and enforced by a series of vocalizations and scent markings (Redmond, 2008).

Unlike most nocturnal primates, tarsiers do not possess a tapetum lucidum, the reflective layer in the back of the eye the produces the ‘cat’s eye’ reflections, which makes them difficult to see at night (Redmond, 2008). This adaptation has likely spared tarsiers from higher levels of poaching, but has made studying them in the wild difficult.

References

Bartlett, T.Q. (2007). The Hylobatidae: Small apes of Asia. In Campbell, C.J., Fuentes, A., Mackinnon, K.C., Panger, M. & Bearder, S.K, editors, Primates in Perspective. Oxford University Press, UK

Kirkpatrick, R.C. (2007). The Asian colobines: Diversity among leaf-eating monkeys. In Campbell, C.J., Fuentes, A., Mackinnon, K.C., Panger, M. & Bearder, S.K, editors, Primates in Perspective. Oxford University Press, UK

Munds, R.A., Nekaris, K.A.I. & Ford, S.M. (2013). Taxonomy of the Bornean slow loris, with new species Nycticebus kayan (Primates, Lorisidae). American Journal of Primatology, 75, pp. 46-56

Nowak, R. M (1999). Primates of the world. Johns Hopkins University Press, USA

Primate Info Net- Library and Information Service of the National Primate Research Center, University of Wisconsin.

Redmond, I. (2008). The Primate Family Tree. Firefly, UK

Rijksen, H.D. & Meijaard, E. (1999). Our vanishing relative: The status of wild orangutans at the close of the 20th century. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, Netherlands